An iterated map model with CaMKII feedback in modeling the force frequency relationship of a cardiac cell

474 viewsDOI:

https://doi.org/10.54939/1859-1043.j.mst.82.2022.142-149Keywords:

Cardiac myocyte; Feedback; Rat heart; CaMKII; Calcium.Abstract

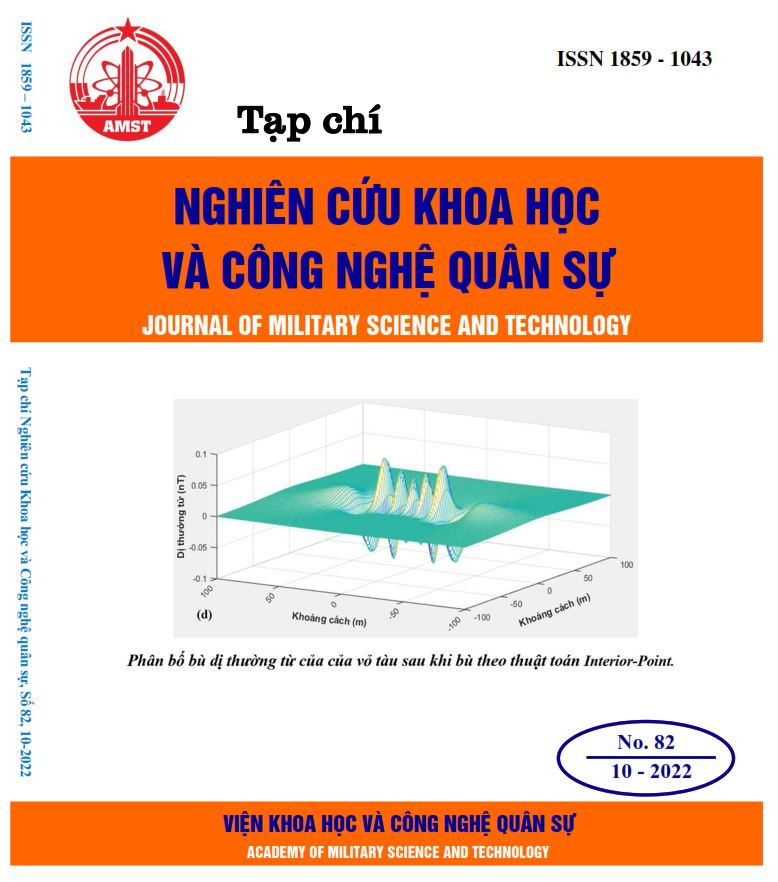

Experiment data on isolated rat hearts shows that the transient behaviors after switching pacing intervals are very complicated with increasing, decreasing, and rebound of the contraction force. The strength of contraction in the heart muscle is strongly related to intracellular free Ca2+ mediated by an action potential. This behavior can be explained by calcium cycling inside the excitable cardiac myocytes coupled with their action potential. The previous and recently proposed models can only explain a short period of time after changing the pacing frequency. Our aim is to develop a simple feedback model based on the role of the enzyme CaMKII to describe the whole dynamic picture captured from experiments.

References

[1]. M. Peirlinck, F. Sahli Costabal, J. Yao, J. M. Guccione, S. Tripathy, Y. Wang, D. Ozturk, P. Segars, T. M. Morrison, S. Levine & E. Kuhl, “Precision medicine in human heart modeling”, Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology volume 20, pp. 803–831, (2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-021-01421-z

[2]. Udelson JE, Stevenson LW, “The future of heart failure diagnosis, therapy, and management”, Circulation 133(25): pp. 2671–2686, (2016). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023518

[3]. E. Sandoe and B. Sigurd, “Arrhythmia - A Guide to Clinical Electrocardiology, chapter 3”, Verlags GmbH, Bingen am Rhein, Germany, (1991).

[4]. Ten Tusscher KHWJ, Noble D, Noble PJ, Panfilov AV, “A model for human ventricular tissue”, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286(4):H1573–H1589, (2004). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00794.2003

[5]. FitzHugh R, “Impulses and physiological states in theoretical models of nerve membrane”, Biophys J 1(6):445 (1961). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(61)86902-6

[6]. Nagumo J, Arimoto S, Yoshizawa S, “Active pulse transmission line simulating nerve axon”, Proc Inst Radio Eng 50: pp. 2061–2070, (1962). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/JRPROC.1962.288235

[7]. C.-H. Luo, Y. Rudy, “A model of the ventricular cardiac action potential. Depolarization, repolarization, and their interaction”, Circ. Res., 68, pp. 1501-1526, (1991). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.68.6.1501

[8]. Luo CH, Rudy Y, “A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. II. Afterdepolarizations, triggered activity, and potentiation”, Circ Res 74: pp. 1097-113, (1994). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.74.6.1097

[9]. Qu Z, Shiferaw Y and Weiss J N, “Nonlinear dynamics of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling: an iterated map study”, Phys. Rev. E 75 011927, (2007). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.75.011927

[10]. Jeffrey J. Fox, Eberhard Bodenschatz, and Robert F. Gilmour, Jr., “Period-Doubling Instability and Memory in Cardiac Tissue”, PRL 89(13), 138101 (2002). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.138101

[11]. Bers, D. M. “Calcium fluxes involved in control of cardiac myocyte contraction” Circ. Res. 87(4): pp. 275–281, (2000). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.87.4.275

[12]. Bers, D. M. “Excitation-contraction coupling and cardiac contractile force”. 2nd ed. Developments in cardiovascular medicine v. 237. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, (2001). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0658-3

[13]. Luis F. Couchonnal and Mark E. Anderson, “The role of calmodulin kinase II in myocardial physiology and disease”, PHYSIOLOGY 23: pp. 151–159, (2008). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00043.2007

[14]. Burkhoff, D., D. T. Yue, M. R. Franz, W. C. Hunter, and K. Sagawa. “Mechanical restitution ofisolated perfused canine left ventricles”. Am. J. Physiol. 246(1 Pt 2):H8–H16, (1984). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.1.H8

[15]. Layland, J., and J. C. Kentish. “Positive force- and [Ca2+] frequency relationships in rat ventricular trabeculae at physiological frequencies”. Am. J. Physiol. 276(1 Pt 2):H9– H18, (1999). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H9

[16]. Lewartowski, B., and B. Pytkowski. “Cellular mechanism of the relationship between myocardial force and frequency of contractions”. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 50(2): pp. 97–120, (1987). doi:0079-6107(87)90005-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0079-6107(87)90005-8

[17]. Dvornikov A. V., Mi Y.C. and Chan C. K., “Transient Analysis of ForceFrequency Relationships in Rat Hearts Perfused by Krebs-Henseleit and Tyrode Solutions with Different [Ca2+]”, Cardiovasc. Eng. Tech., 3, 203 (2012). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13239-012-0091-9

[18]. D. M. Le, Alexey V. Dvornikov, Pik-Yin Lai, and C. K. Chan, “Predicting selfterminating ventricular fibrillations in an isolated heart”, EPL, 104, 48002 (2013). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/104/48002